Let's consider this from the perspective of avian evolution for a moment. Birds originated in the late mesozoic (245-66 mya) and differentiated in the early cenozoic (66-37 at the end of the eocene). The best example of this is archaeopteryx from the upper jurassic (208-144 mya). The most amazing thing about archaeopteryx is that it had feathers. Why is that amazing? Archaeopteryx share a large number of similarities to dinosaurs such as composgnathus. Archaeopteryx does not have a large sternum as in birds, its bones are thickwalled and lack the pneumatic ducts seen in birds. The front limbs show typically reptilian features such as three fully developed digits, flexible carpus and unaltered radius and ulna (in humans this is the forearm). Other characteristics similar to that of reptiles include the retention of teeth and limited fusion of bones in the skull. Birds have a unique pelvic morphology and also posses a furcula (wishbone). Archaeopteryx has a birdlike pelvis and has a furcula - unfortunately, these two traits have been found in several theropod dinosaurs. An Asian genera, for example, has a posteriorly rotated pubis similar to that in birds. Others have fused clavicles that form a wishbone structure. The most birdlike features of Archaeopteryx, not including the feathers, are in the rear limbs. The head of the femur is turned inwards, the knee and ankle joints form simple hinge joints and three of the toe digits face forwards while the first toe digit is turned to the rear. Some of these traits are found in theropods as well. So where does that leave us in the reptile-bird transition? We have some traits that link Archaeopteryx firmly with reptiles, others are found in both birds and reptiles, and none link Archaeopteryx to birds only. With the recent oviraptor discovery, we now have a dinosaur that lays eggs in a fashion intermediate between the primitive reptillian pattern and birds.

Which, of course, brings us to horses.

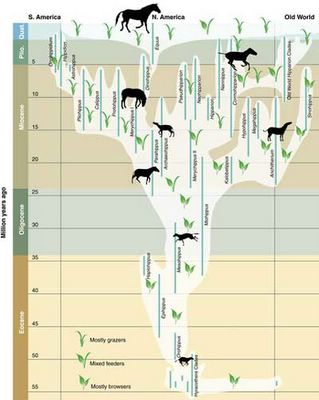

The above is a neat chart (which I swiped from Pharyngula ) that shows the broad outlines of horse evolution. Horse evolution is really fascinating because there are so many different things all going on at once. Some species were increasing in size, others were decreasing in size. Some were reducing the number of toes, others weren't. Some were increasing the thickness of the enamel on their teeth and increasing the size of the ridges on thier teeth. Some were browsers, others were grazers and still others were mixed feeders. At this point the parallels between horse evolution and the reptile-bird transition should be obvious (and to go even further the reptile-mammal transition). With horse evolution we have several genera with a mosaic of traits some of which we see in modern horses. In the reptile-bird we also have a wide variety of species with traits that link them to modern birds, although none of them had the complete set of characteristics that we use to define the class Avis.

The above discussion is a prelude to my directing you to these two articles:

Gould on Phyla (while you are at Pharyngula check out the post on hot-blooded crocodiles)

and Down With Phyla .

The point you should take with you to these other articles is that, although Archaeopteryx presents some radically new characteristics that define a new class, it is still just an animal trying to survive as best it can. It is linked to other animals by the traits it shares with them. Perhaps the biggest difference between Archaeopteryx and the other theropods is that it had more traits that it shared with birds than the other theropods did. It is very easy to forget the animal and reify the mosaic of traits that came to be called Avis. This is where, in my opinion, creationists tend to make their biggest mistake in talking about "Macroevolution".

Bibliography

Wicander, R and Monroe, J. (1989)Historical Geology: Evolution of the Earth and Life Through Time

Carroll, R. (1988) Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution